Dutch Provos

|

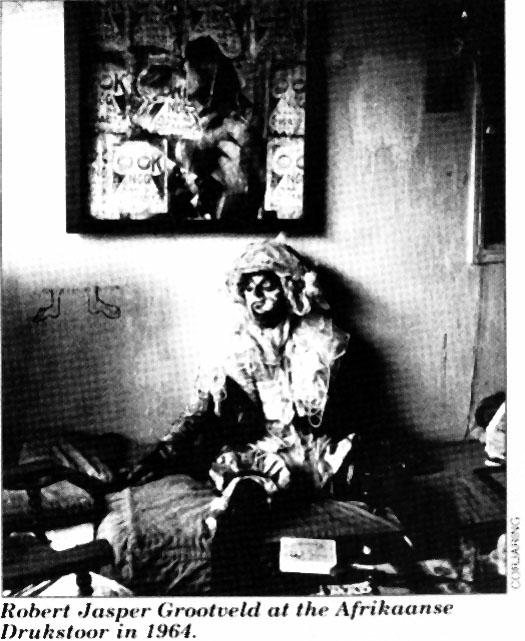

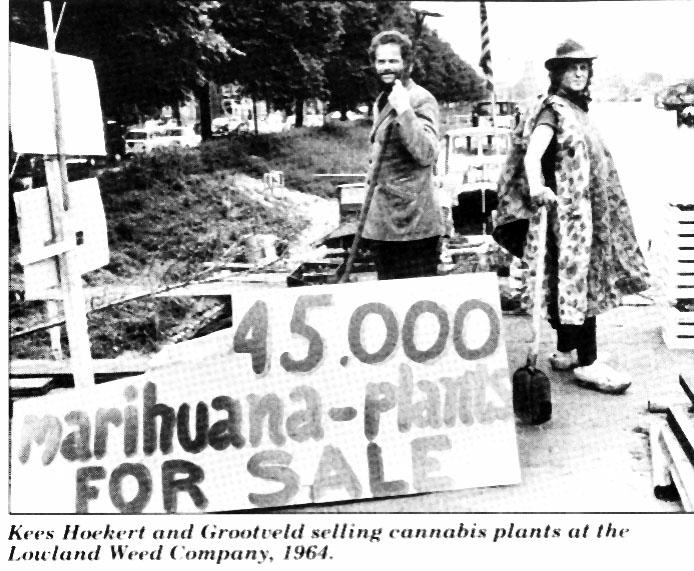

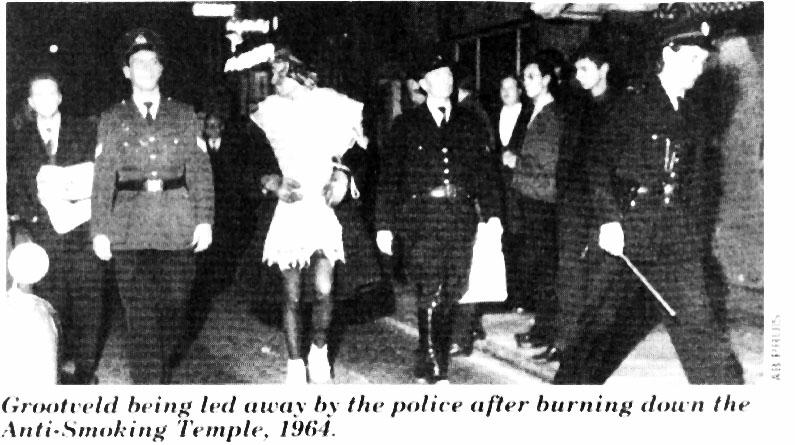

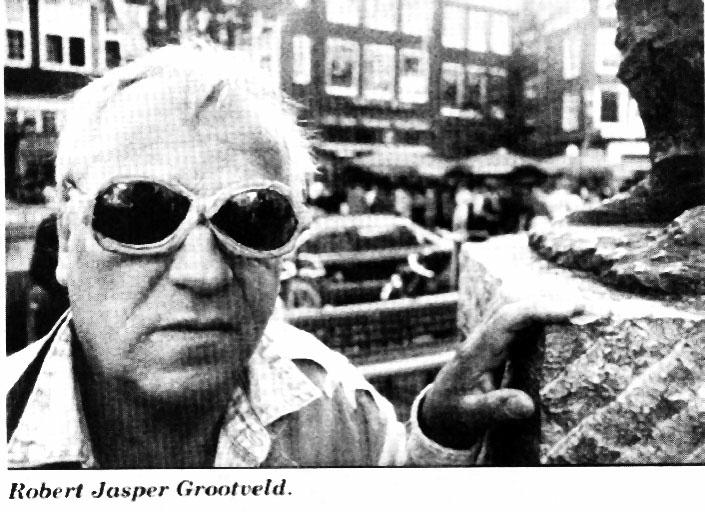

The following year, Grootveld arid artist Fred Wessels opened the "Afrikaanse Druk Stoor," where they sold both real and fake pot. The marihuette game became the model for future Provo tactics. Surprisingly, games proved to be an effective way of shattering the smug self-righteousness of the authorities. The police would usually overreact, making themselves seem ridiculous in the process. There was, however, a seriousness underlying the method. The ultimate aim was to change society for the better. In the late '50s. Grootveld was already well-known as a kind of performance artist. His inspiration, he claimed, derived from a pilgrimage to Africa, where he'd purchased a mysterious medicine kit formerly owned by a shaman. Somehow, the kit helped Grootveld formulate a critique of Western society, which, he came to believe, was dominated by unhealthy addictions A short hospital stay soon convinced Grootveld that the worst of these was cigarette smoking "All those grown-up patients, begging and praying for a cigarette was a disgusting sight," he recalls. (Even after this realization, however, Grootveld remained a chain-smoker.) Smoking, according to Grootveld, was an irrational cult, a pointless ritual forced upon society by the tobacco industry for the sole purpose of making profits. The bosses of the "Nico-Mafia" were the high priests of a "cigarette-cult"; advertisements arid commercials were their totems. Ad agencies were powerful wizards, casting magic spells over a hypnotized public. At the bottom of the heap lay the addicted consumers, giving their lives through cancer to the great. "NicoLord." Grootveld began a one-man attack on the tobacco industry. First, he scrawled the word "cancer" in black tar over every cigarette billboard in town. For this, he was arrested and put in jail. After his release, Grootveld began going into tobacco shops armed with a rag soaked in chloroform. "I spread that terrible hospital odor all around," he says. "I asked if I could make a call and spent hours on the phone, gasping, coughing and panting, talking about hospitals and cancer arid scaring all the customers. A rich, eccentric restaurant owner named Klaas Kroese decided to support Grootveld's anti-smoking crusade. He provided him with a studio, which Grootveld dubbed the "Anti-Smoking Temple." Declaring himself 'The First Anti-Smoke Sorcerer," Grootveld started holding weekly black masses with guest performances by poet Johnny the Selfkicker, writer Simon Vinkenoog [see HIGH TIMES, June '86], and other local underground artists. But Grootveld was soon disappointed by the small media coverage these performances received, blaming it all on the Nico-Mafia who controlled the press. He decided to do something really sensational. After a passionate speech and the singing of the "Ugge Ugge" song, the official anti-smoking jingle, Grootveld set the Anti-Smoking Temple on fire, in front of a bewildered group of bohemians, artists, and journalists. At first everyone thought it was a joke, but when Grootveld started spraying gasoline around the room, the audience fled to safety. Grootveld himself came perilously close to frying, saved only by the efforts of the police who came to rescue him. Although the crusade had only begun, the fire cost him the support of Kroese, his first patron.

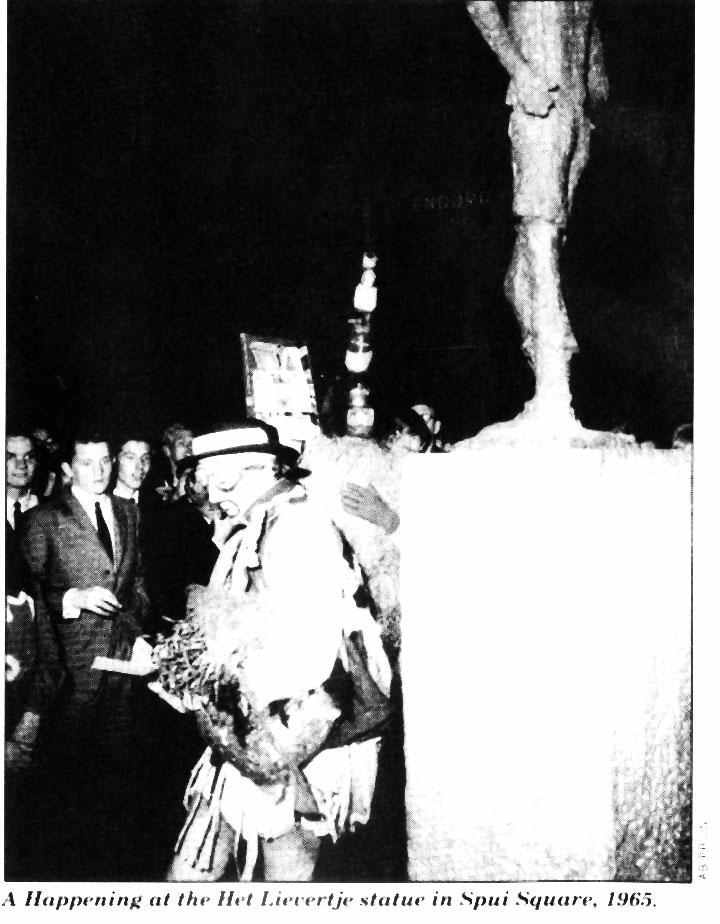

Writer Harry Mulisch described it this way: "While their parents, sitting on their refrigerators and dishwashers, were watching with their left eye the TV, with their right eye the auto in front of the house, in one hand the kitchen mixer, in the other De Telegraaf, their kids went at Saturday night to the Spui Square . . . And when the clock struck twelve, the high Priest appeared, all dressed up, from some alley and started to walk Magic Circles around the nicotinistic demon, while his disciples cheered. applauded and sang the Ugge Ugge song."

Grootveld read the first Provo manifesto and decided to cooperate with the publishers. "When I read the word anarchism in that first pamphlet, I realized that this outdated, 19th century ideology would become the hottest thing in the '60s," he recalls. The leaflets were followed by more elaborate pamphlets announcing the creation of the White Plans. Constant Nieuwenhuis, another artist, was instrumental in shaping the White Philosophy, which considered work (especially mundane factory labor) obsolete. Provo's renunciation of work appealed to the Nozems - and marked an important ideological split with capitalism, communism and socialism, all of which cherished work as a value in itself. Provo, however, sympathized more with Marx' anarchist son-in-law Paul Lafargue, author of "The Right to Laziness." The. most famous of all white plans was the White Bike Plan, envisioned as the ultimate solution to the "traffic terrorism of a motorized minority." The brain-child of Industrial designer Luud. Schimmelpenninck, the White Bike Plan proposed the banning of. environmentally noxious cars from the inner city, to be replaced by bicycles. Of course, the bikes were to be provided free by the city. They would be painted white and permanently unlocked, to secure their public availability. Schimmelpenninck calculated that,. even from a strictly economic point of view, the plan would provide great benefits to Amsterdam. The Provos decided to put the plan into action by providing the first 50 bicycles. But the police immediately confiscated them, claiming they created an invitation to theft. Provo retaliated by stealing a few police bikes. The White Victim Plan stated that Anyone causing a fatal car accident should be forced to paint the outline of their victim's body on the pavement at the site of the accident. That way, no one could ignore the fatalities caused by automobiles.

Some White Plans were elaborate, others were just flashes of inspiration. "It seemed that proposing a White Plan was almost a necessary exam to becoming a Provo," says Grootveld. The most hilarious of all was the White Chicken Plan proposed by a Provo subcommittee called Friends of the Police. After the police began responding to Provo demonstrations with increased violence. the Provos attempted to alter the image of the police, who were known as "blue chickens." The new white chickens would be disarmed, ride around on white bicycles, and distribute first aid, fried chicken, and free contraceptives.

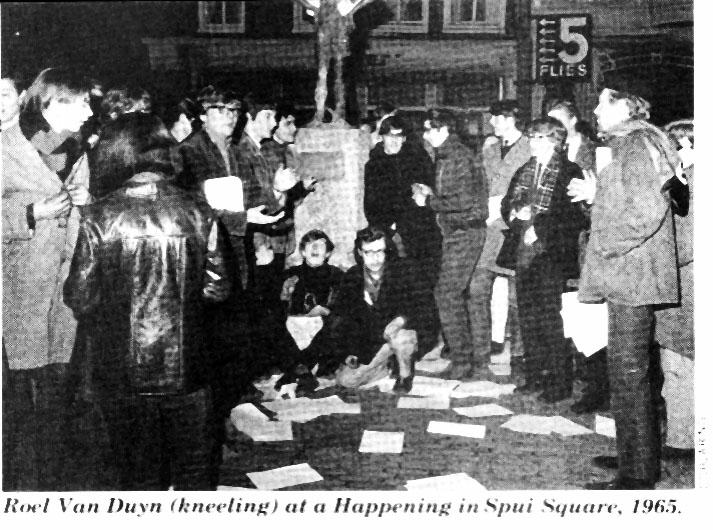

Van Duyn's theories of modem life were quite similar to Grootveld's: labor and the ruling class had merged into one big, gray middle-class. This boring bourgeoisie was living in a catatonic state, its creativity burnt out by TV. "It is impossible to have the slightest confidence in that dependent, servile bunch of roaches and lice," concluded Van Duyn. The only solution to this problem lay with the Nozems, artists, dropouts, streetkids and beatniks, all of whom shared a non-involvement with capitalist society. It was Provo's task to awaken their latent instincts for subversion. to turn them on to anarchist action. As later became clear, Provo didn't really enlighten the street crowd, although they did offer an opportunity to intellectuals and punks alike to express their feelings of frustration and rage. Van Duyn's writings combined an equal mixture of pessimism and idealism. Too much a realist to expect total revolution, he tended to follow a more pragmatic and reformist strategy. Eventually he advocated participating in Amsterdam council elections. Other Provos denounced this as an outrageous betrayal of anarchist ideals. One Provo leaflet hit the newsstands folded between the pages of De Telegraaf, Amsterdam's biggest newspaper. The perpetrator was immediately fired from the airport newsstand where he worked. No big deal for a Provo. It was important to demonstrate a disdain for careerism in general. When the next leaflet, Provokaatsie #3, was published, it aroused indignation all over the Netherlands by alluding to the Nazi past of some members of the Royal House, a sacred institution in Dutch society. Provos threw the leaflet into the royal barge as it toured the canals of Amsterdam. Provokaatsie #3 was the first in a series of publications that were immediately confiscated by police. The official excuse was that Provo had used some illustrations without permission. A lawsuit followed and Van Duyn was held responsible. But instead of showing up in court, Van Duyn sent a note stating it was ". . . simply impossible to hold one single individual responsible. Provo is the product of an everchanging, anonymous gang of subversive elements . . . . Provo doesn't recognize copyright, as it is just another form of private property which is renounced by Provo . . . . We suspect that this is an indirect form of censorship while the State is too cowardly to sue us straight for lese majeste [an offense violating the dignity of the ruler]. . . . By the way, our hearts are filled with a general contempt for authorities and for anyone who submits himself to them. . . ." In July 1965, the first issue of Provo magazine appeared. "It was very shocking to the establishment," recalls Grootveld. "They realized we were not mere dopey scum but were quite capable of some sort of organization." The first issue contained out-of-date, 19th century recipes for bombs, explosives and boobytraps. Firecrackers included with the magazine provided an excuse for the police to confiscate the issue. Arrested on charges of inciting violence, editors Van Duyn, Stoop, Hans Metz and Jaap Berk were released a few days later.

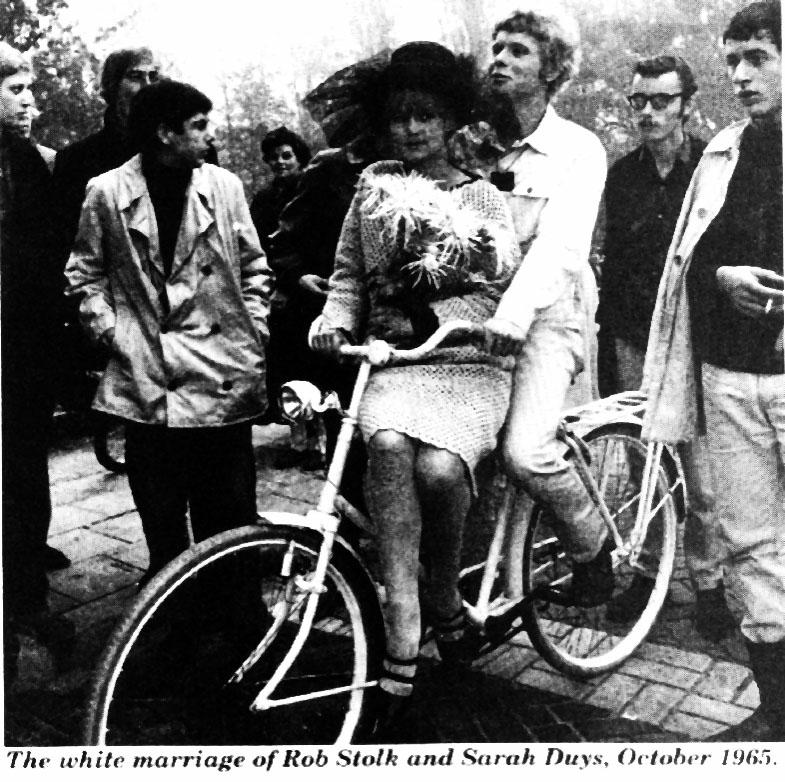

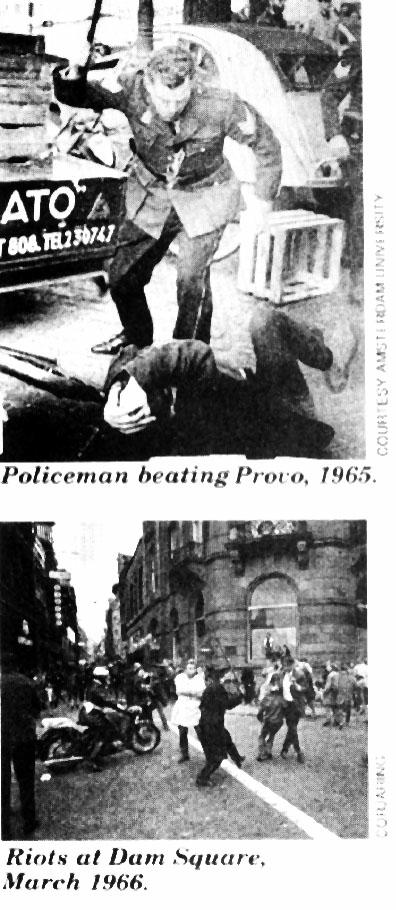

By July 1965, Provo had become the national media's top story, mostly due to overreaction by the city administration, who treated the movement as a serious crisis. Even though only a handful of Provos actually existed, due to Provo media manipulation it seemed as though thousands of them were roaming the streets. "We were like Atlas, carrying an image that was blown up to huge proportions," recalls Van Duyn. At the early Spui Square Happenings, the police usually responded by arresting Grootveld, which was no big deal. Grootveld was considered a harmless eccentric and always treated with respect. Privately, he got along quite well with the police. "They gave me coffee and showed me pictures of their kids," he says. And Grootveld remained grateful to the police for rescuing him from his burning temple. However, trouble started at the end of July. A few days before, the White Bike Plan had been announced to the press. The police were present, but hadn't interfered. At an anti-auto happening the next Saturday, however, the police showed up in great numbers. As soon as some skirmishing began, the police tried to break up the crowd. The following week, after sensational press coverage, a huge crowd gathered at Spui Square. Again the police tried to disperse the crowd, but this time serious fighting broke out, resulting in seven arrests. The next day De Telegraaf's headlines screamed, "The Provos are attacking!" Suddenly, the Provos were a national calamity. In August 1965, some Provos met with the police to discuss the violent interventions in the Happenings. "Since Amsterdam is the Magic Center, it is of great cultural importance that the Happenings will not be disturbed," declared the Provos in a letter to the commander of police. Unfortunately, the talks produced no results. "We stared at each other in disbelief like we were exotic animals," says Van Duyn. The same night, the police surrounded the little statue in Spui Square, Rob Stolk recalls, "like it was made out of diamonds and Dr. No or James Bond wanted to steal it." About 2,000 spectators were present, all waiting for something to happen. At exactly twelve o'clock, not Grootveld, but two other Provos showed up. As they tried to lay flowers at the Het Lievertje statue, the crowd cheered. The police arrested them on the spot, after which a riot broke out. Thirteen were arrested, four of whom had nothing to do with Prove, but just happened to be hanging around the square. They all ended up serving between one and two months in jail. In September 1965, Provo focused their actions on another statue, the Van Heutz monument.. Although Van Heutz is considered by most Dutch to be a great hero of their colonial past, Provo branded him an imperialistic scavenger and war criminal. The following month the first anti-Vietnam war rallies were organized by leftist students who were slowly joining Provo. "Our protests against the Vietnam war were from a humanistic point of view," recalls Stolk. "We criticized the cruel massacres, but didn't identify with the Vietcong like Jane Fonda. That's why later on we didn't wind up on aerobics videos." Although the Happenings at the Spui Square were still going on, the Vietnam demonstrations became the big story of 1965. Hundreds were arrested every week. Meanwhile, the Provo virus was spreading throughout Holland. Every respectable provincial town boasted its local brand of Provos, all with their own magazines and statues around which Happenings were staged. At the end of the year, the administration changed tactics. Instead of violent police interventions, they tried to manage the Provos. Obsolete laws were uncovered and turned against Provo. But when a demonstration permit was refused on this basis, the Provos showed up with blank banners and handed out blank leaflets. They still got arrested. Provo Koosje Koster was arrested for handing out raisins at a Spui Happening. The official reason? Bringing the public order and safety into serious jeopardy. Public opinion on the Provos began to get more polarized. Although many were in favor of even harsher measures against the rabble-rousers, a growing segment of the public sympathized with the Provos and began having serious doubts about police overreaction. The monarchy became the ultimate establishment symbol for the Provos to attack. Royal ceremonies offered ample opportunities for satire. During "Princess Day," when an annual ceremonial speech was delivered by the queen. Provo made up a fake speech, in which Queen Juliana declared she'd become an anarchist and was negotiating a transition of power with Provo. Provo Hans Tuynman invited the Queen to hold an intimate conversation in front of the palace. where he and some other Provos had assembled some comfortable chairs. Although the Queen did not show, the police did, quickly breaking up the Happening.

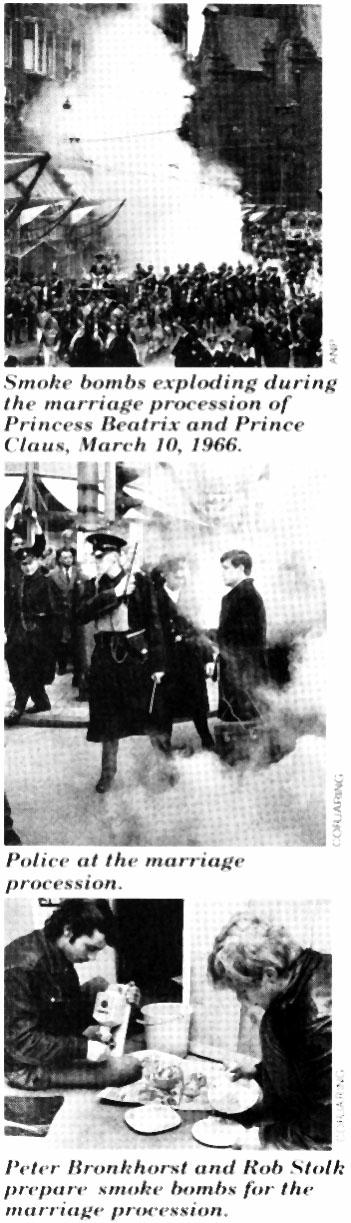

"Grootveld objected to this corruption of his symbolic Klaas mythology," recalls Jef Lambrecht. "He wanted to keep KIaas pure and undefinable, but the link was soon established." The Provos spent months preparing for the March wedding. A bank account was opened to collect donations for an anti-wedding present. The White Rumor Plan was put into action. Wild and ridiculous rumors were spread through Amsterdam. It became widely believed that the Provos were preparing to dump LSD in the city water supply, that they were building a giant paint-gun to attack the wedding procession, that they were collecting manure to spread along the parade route, and that the royal horses were going to be drugged. Although Provo was actually planning nothing more than a few smoke bombs, the police expected the worst acts of terrorism imaginable. Foreign magazines offered big money to Provos if they would disclose their secret plans before the wedding, plans that didn't exist. A few days before the wedding, all the Provos mysteriously disappeared. They did this simply to avoid being arrested before the big day. Meanwhile, the authorities requested 25,000 troops to help guard the parade route. On the day of the wedding, Amsterdam - the most anti-German and anti-monarchist city in the country - was not in the mood for grand festivities. Half the City Council snubbed the official wedding reception. A foreign journalist put it this way: "The absence of any decorated window, of any festive ornament, is just another expression of the indifference of the public." Miraculously, by dressing up like respectable citizens, the Provos managed to sneak their smoke bombs past the police and army guards. "The night before, the cops made a terrible blooper by violently searching an innocent old man who was carrying a suspicious leather bag. So the fools gave orders not to search leather bags any more, fearing dirty Provo tricks!" says Appie Pruis, a photographer. The first bombs went off just behind the palace as the procession started. Although the bombs were not really dangerous (they were made from sugar and nitrate). they put out tremendous clouds of smoke, which were viewed on television worldwide. "It was a crazy accumulation of insane mistakes. Most of the police had been brought in from the countryside, and so were totally unable to identify the Provos." A violent police overreaction ensued, witnessed by foreign journalists, many of whom were clubbed and beaten in the confusion. The wedding turned into a public relations disaster. "Demonstrations of Provo are Amsterdam's bitter answer to monarchist folklorism," commented a Spanish newspaper. The week after the wedding, a photo exhibition was held documenting the police violence. The guests at the exhibition were attacked by the police and severely beaten. Public indignation against the police reached new peaks. Many well-known writers and intellectuals began requesting an independent investigation of police behavior. In June, after a man was killed in a labor dispute, it seemed as if a. civil war was ready to erupt. According to De Telegraaf, the victim was killed not by the police, but by a co-worker, an outrageous lie. A furious crowd stormed the offices of the paper. For the first time, the proletariat and Provo were fighting on the same side. By the middle of 1966, repression was out of control. Hundreds of people were arrested every week at Happenings and anti-Vietnam rallies. A ban on demonstrations caused them to grow even bigger. Hans Tuynman was turned into a martyr after being sentenced to three months in jail for murmuring the word "image" at a Happening. Yet around the time, a Dutch Nazi collaborator, a war criminal responsible for deporting Jews, had been released from prison and a student fraternity member received only a small fine for manslaughter. Finally, in August 1966, a congressional committee was established to investigate the crisis. The committee's findings resulted in the Police Commissioner's firing. In May 1967, the mayor of Amsterdam, Van Hall, was "honorably" given the boot, after the committee condemned his policies. Strangely enough, Provo, which had demanded the mayor's resignation for over a year, liquidated within a week of his dismissal. The reason for Provo's demise, which was totally unexpected by outsiders, was its increasing acceptance by moderate elements, and growing turmoil within its ranks. As soon as Provo began participating in the City Council elections, a transformation occurred. A Provo Politburo emerged, consisting of VIP Provos who began devoting most of themselves to political careers. Provos toured the country, giving lectures and interviews. When the VIP Provos were out of town attending a Provo congress, Stolk staged a fake palace coup by announcing that a new Revolutionary Terrorist Council had taken power. Van Duyn reacted furiously, not realizing it was a provocation against Provo itself. When the Van Heutz monument was damaged by bombs, Provo declared that "although they felt sympathy for the cause, they deeply deplored the use of violence." The division between the street Provos and the reformist VIPs began growing wider. Some Provos returned to their studies,. others went hippie and withdrew from the movement. Provo was a big hit as long as it was considered outside of society. But as soon as the establishment began embracing it, the end was near. Moderate liberals began publicly defending It and social scientists began studying the movement. The former Secretary. of Transportation joined forces with Provo. "As a real supporter, he should have proposed a crackdown on Provo," Van Duyn said later. Provo's proposal to establish a playground for children was now greeted by the City Council with great enthusiasm. The real sign of Provo's institutionalization, however, was the installation of a "speakers-corner" in the park. Van Duyn encouraged this development, but Stolk saw it as a form of repressive tolerance - the Provos were now free, free to be ignored. "Understanding politicians, well-intentioned Provologists and pampering reverends, they were forming a counter-magic circle around us to take away our magic power," says Stolk. So Stolk and Grootveld decided to liquidate Provo. "The power and spirit had vanished," says Grootveld. "Provo had turned into a dogmatic crew. Provo had degenerated into a legal stamp of approval." At the liquidation meeting, Stolk said: "Provo has to disappear because all the Great Men that made us big have gone," a reference to Provo's two arch-enemies, the mayor and commissioner of police. Provo held one last stunt A white rumor was spread, that American. universities wanted to buy the Provo archives, documents that actually didn't exist. Amsterdam University, fearing that the sociological treasure might disappear overseas, quickly made an offer the Provos couldn't refuse. [sidebar:]

The Original Provos: Where Are They Now?

[End of article]

Sincerely yours,

[End] |

It's no secret that Holland has the most liberal drug laws in the

world, especially when it comes to cannabis. What you may not realize,

however, is that these laws were enacted thanks to the efforts of the

Dutch Provos. The Provos set the stage for the creation of the Merry

Pranksters, Diggers, and Yippies. They were the first to combine

non-violence and absurd humor to create social change. They created the

first "Happenings" and "Be-Ins." They were also the first to actively

campaign against marijuana prohibition. Even so, they remain relatively

unknown outside of Holland. Now, for the first time, their true story

is told.

It's no secret that Holland has the most liberal drug laws in the

world, especially when it comes to cannabis. What you may not realize,

however, is that these laws were enacted thanks to the efforts of the

Dutch Provos. The Provos set the stage for the creation of the Merry

Pranksters, Diggers, and Yippies. They were the first to combine

non-violence and absurd humor to create social change. They created the

first "Happenings" and "Be-Ins." They were also the first to actively

campaign against marijuana prohibition. Even so, they remain relatively

unknown outside of Holland. Now, for the first time, their true story

is told. "Provo"

was actually first coined by Dutch sociologist Buikhuizen in a

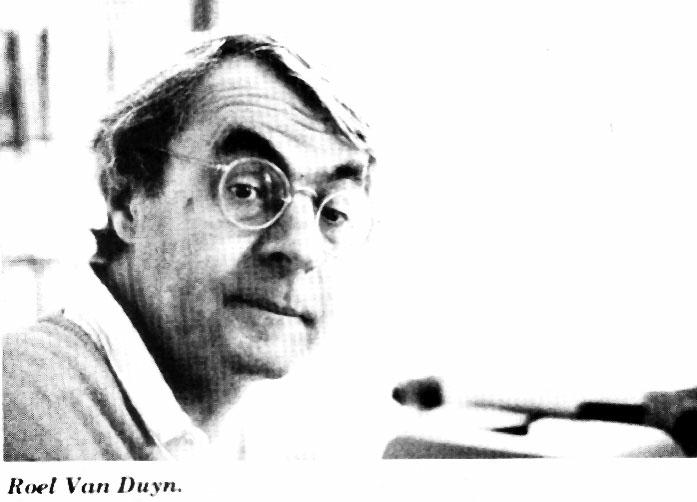

condescending description of the Nozems. Roel Van Duyn. a philosophy

student at the University of Amsterdam, was the first to recognize the

Nozems' slumbering potential. "It is our task to turn their aggression

into revolutionary consciousness," he wrote in 1965.

"Provo"

was actually first coined by Dutch sociologist Buikhuizen in a

condescending description of the Nozems. Roel Van Duyn. a philosophy

student at the University of Amsterdam, was the first to recognize the

Nozems' slumbering potential. "It is our task to turn their aggression

into revolutionary consciousness," he wrote in 1965. The

Provo phenomenon was an outgrowth of the alienation and absurdity of

life hi the early '60s. It was irresistably attractive to Dutch youth

and seemed like it would travel around the world. However, in only a

few short years it disappeared, choked on its own successes.

The

Provo phenomenon was an outgrowth of the alienation and absurdity of

life hi the early '60s. It was irresistably attractive to Dutch youth

and seemed like it would travel around the world. However, in only a

few short years it disappeared, choked on its own successes. In

1964, Grootveld moved his black masses, now known as "Happenings," to

nearby Spui Square. At the center of the square was a small statue of a

child, "Het Lievertje." By coincidence, the statue had been

commissioned by a major tobacco firm. For Grootveld, this bit of

evidence proved the insidious infiltration of the nico-dope syndicates.

Every Saturday, at exactly midnight, Grootveld began appearing in the

square, wearing a strange outfit and performing for a steadily growing

crowd of Nozems, intellectuals, curious bypassers and police.

In

1964, Grootveld moved his black masses, now known as "Happenings," to

nearby Spui Square. At the center of the square was a small statue of a

child, "Het Lievertje." By coincidence, the statue had been

commissioned by a major tobacco firm. For Grootveld, this bit of

evidence proved the insidious infiltration of the nico-dope syndicates.

Every Saturday, at exactly midnight, Grootveld began appearing in the

square, wearing a strange outfit and performing for a steadily growing

crowd of Nozems, intellectuals, curious bypassers and police. One

night in May 1965, Van Duyn appeared at one of the Happenings and began

distributing leaflets announcing the birth of the Provo movement.

"Provo's choice is between desperate resistance or apathetic

perishing," wrote Van Duyn. "Provo realizes eventually it will be the

loser, but won't let that last chance slip away to annoy and provoke

this society to its depths . . ."

One

night in May 1965, Van Duyn appeared at one of the Happenings and began

distributing leaflets announcing the birth of the Provo movement.

"Provo's choice is between desperate resistance or apathetic

perishing," wrote Van Duyn. "Provo realizes eventually it will be the

loser, but won't let that last chance slip away to annoy and provoke

this society to its depths . . ." Other

White Plans included the White Chimney Plan (put a heavy tax on

polluters and paint their chimneys white), the White Kids Plan (free

daycare centers), the White Housing Plan (stop real estate speculation)

and the White Wife Plan (free medical care for women).

Other

White Plans included the White Chimney Plan (put a heavy tax on

polluters and paint their chimneys white), the White Kids Plan (free

daycare centers), the White Housing Plan (stop real estate speculation)

and the White Wife Plan (free medical care for women). The

police failed to appreciate this proposal. At one demonstration they

seized a dozen white chickens which had been brought along for symbolic

effect.

The

police failed to appreciate this proposal. At one demonstration they

seized a dozen white chickens which had been brought along for symbolic

effect. Actually,

Provo had an ambivalent attitude toward the police, viewing them as

essential non-creative elements for a successful Happening. Grootveld

called them "co-happeners." "Of course, it is obvious that the cops are

our best pals," wrote Van Duyn. "The greater their number, the more

rude and fascist their performance, the better for us. The police, just

like we do, are provoking the masses . . . . They are causing

resentment. We are trying to turn that resentment into revolt."

Actually,

Provo had an ambivalent attitude toward the police, viewing them as

essential non-creative elements for a successful Happening. Grootveld

called them "co-happeners." "Of course, it is obvious that the cops are

our best pals," wrote Van Duyn. "The greater their number, the more

rude and fascist their performance, the better for us. The police, just

like we do, are provoking the masses . . . . They are causing

resentment. We are trying to turn that resentment into revolt." The

climax of this anti-royal activity came in March 1966, when Princess

Beatrix married a German, Claus von Amsberg, a former member of

Hitlerjugend, the Nazi youth organization. Coincidentally, Grootveld

had been doing performances based on "the coming of Klaas," a mythical

messiah. Sinterklaas, the Dutch version of Santa Claus, and Klaas

Kroese, Grootveld's former sponsor, served as the inspirations for

these performances. But by March, Proyos identified the coming of Klaas

with the arrival of Von Amsberg.

The

climax of this anti-royal activity came in March 1966, when Princess

Beatrix married a German, Claus von Amsberg, a former member of

Hitlerjugend, the Nazi youth organization. Coincidentally, Grootveld

had been doing performances based on "the coming of Klaas," a mythical

messiah. Sinterklaas, the Dutch version of Santa Claus, and Klaas

Kroese, Grootveld's former sponsor, served as the inspirations for

these performances. But by March, Proyos identified the coming of Klaas

with the arrival of Von Amsberg. After

Provo dissolved, the main characters went their own way. Van Duyn

continued in politics and founded the anarchistic "Kabouter" party. The

Kabouters (or "gnomes" in Dutch) successfully put several members on

the Amsterdam city council. Currently, Van Duyn is involved with the

Green Party.

After

Provo dissolved, the main characters went their own way. Van Duyn

continued in politics and founded the anarchistic "Kabouter" party. The

Kabouters (or "gnomes" in Dutch) successfully put several members on

the Amsterdam city council. Currently, Van Duyn is involved with the

Green Party. Schimmelpenninck

owns a successful industrial design studio. He designed and developed a

small electric car, the Witkar, which never became a big hit due to the

high cost of production.

Schimmelpenninck

owns a successful industrial design studio. He designed and developed a

small electric car, the Witkar, which never became a big hit due to the

high cost of production.