|

Misha Buster

In the 1970s, when Soviet ideology and five-year plans still reigned, Soviet fashion, and more particularly the industrial production of clothing, was hopelessly cut off from the foreign fashion industry, and there had been several attempts to reign it in. All this was despite the existence of a whole constellation of talented professions working at the fashion theaters, where seasonal shows of collections were held for the benefit of the party nomenklatura in special ateliers, while the general public was offered sewing patterns in specialist publications with conceptual, didact ic titles such as “You Sew” and “I Sew.”

During perestroika, in the second half of the 1980s, designers were permitted to attach their own names to their designs, and clothing stores opened at fashion houses where previously only the Soviet elite could order items. But even this sudden shift could not change the overall situation — it was all too late and in vain.

The Soviet people, who for years had sewn and knitted based on patterns in Polish and Soviet fashion magazines, had experienced long years when there was a deficit of fashionable items, and as a result had become somewhat disenchanted with the slogan “Soviet is the best.” Fashion was declared a “bourgeois relic,” but it was available through black marketeers and underground manufacturers, and it captured the imaginations of the Soviet people ever more. A boom among young people and music fans and the appearance of cooperatives and suitcase traders, as well as of mass-produced clothing that had been legally produced or imported, definitively destroyed any hopes that fashions produced in Soviet factories could catch up with the West. People stood for hours in long lines to buy imported brands, spoke only about imports, and even in Soviet films a new set of characters wore clothing that was hard to find on the shelves of Soviet stores.

It was amid these conditions that the phenomenon of “alternative fashion” emerged. The term itself became official when it appeared on the pages of Mlodosc, a Polish magazine.

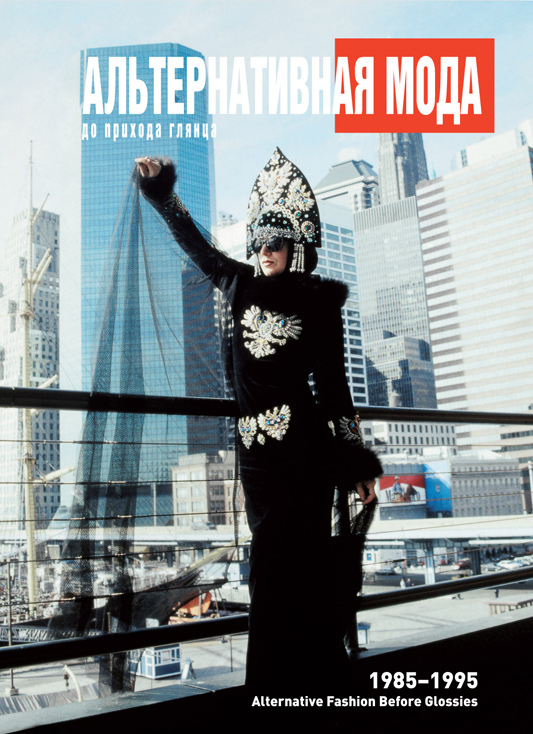

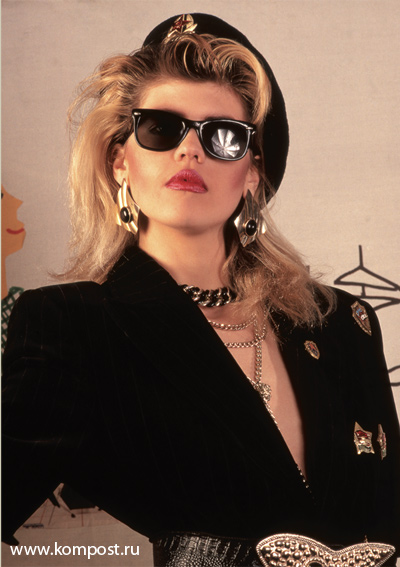

Alternative fashion was wild and untamed, flaring up suddenly like a chemical reaction among the various underground creative groups, who had claimed a place on the rock scene, in squats and on official stages with lightning speed. But we mightwonder: What does it mean to speak of “fashion” in a society cut off from all information, and which was behind an Iron Curtain that was now collapsing? In this context fashion was rumors, gossip, ideas and legends that were brought to life by designers and fashionistas in extravagant outfits worn on amateur catwalks and on the street. In essence creating a fashion theaterfor the new aesthetic, they balanced on the border between performance and a fashion show. And all this survived until the advent, in the new Russia of the 1990s, of glossy magazines and renewed efforts to curb freedom in fashion via the dictates of editors and official shows at fashion weeks.

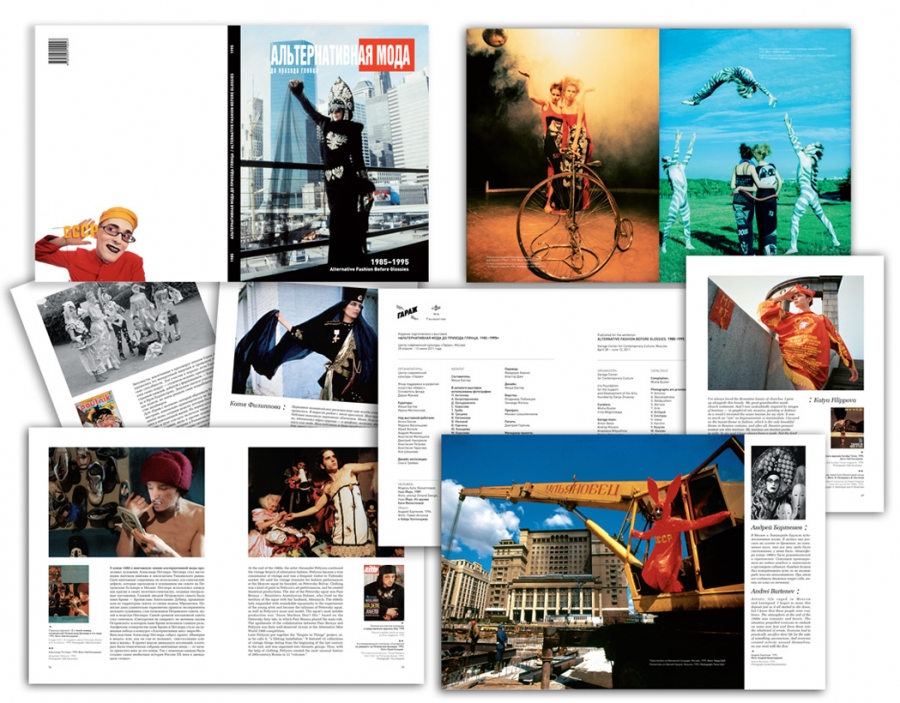

As such, the archive project www.kompost.ru, which previously documented the emergence of 1980s street styles at an exhibition

and published the 500‑page book “Hooligans-80,” has created a photographic history of alternative fashion.

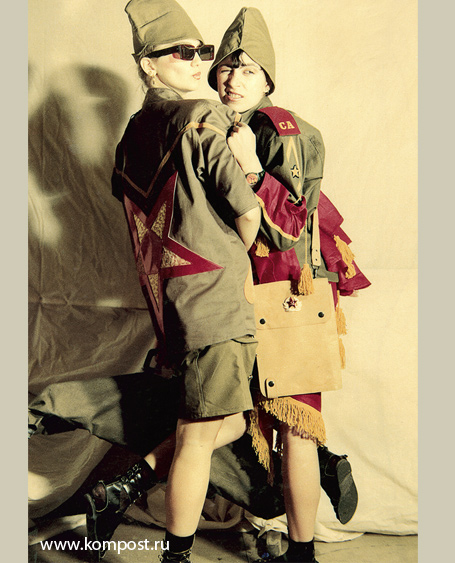

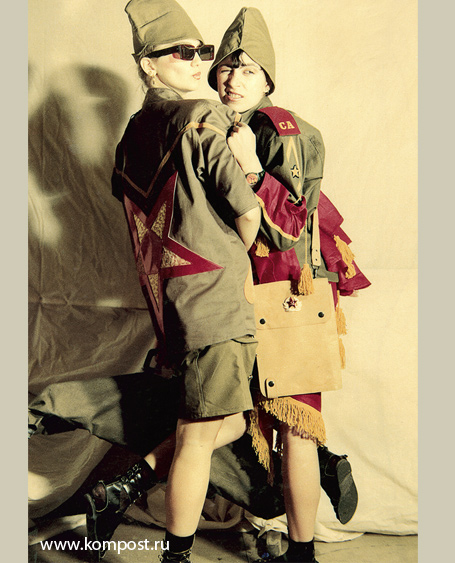

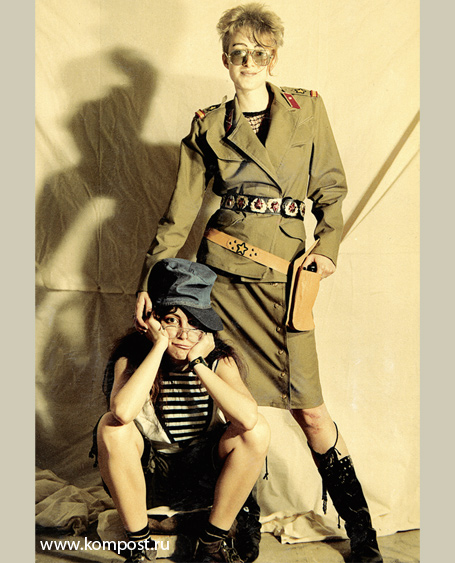

By the 1980s, residents of the Soviet Union had an utterly confused idea of fashion. An aesthetic war was being waged above Soviet society between “Soviet couture” and the fashions offered by black marketeers. Soviet magazines promoted a quasi-Western style and published patterns and faded photographs. There was a new wave of sporting and youth fashions that was not at all dictated from on high. Thus instead of mainstream fashion there were sudden crazes for minis, flares and jeans. Certain social groups became trendsetters and had links to the black market and retailers, and the rest of the country’s inhabitants were forced to express themselves with whatever they could sew, throw together or get their hands on. Meanwhile a whole set of somewhat laughable fashions were produced that in our time would create a frenzy, considering the current boom of youth anti-fashion. But even amid this jumble of tastes it was possible to identify the basic Soviet Puritanism that had been fostered in the population, which traditionally valued sturdy, strong clothing over fleeting seasonal trends. True fashion, or that which was understood by true fashion, was far from the standards that gave birth to the active burst of self-creation. Against this variegated background, the sole stylish and notable outfits were the ceremonial army and navy uniforms, a genuine achievement — perhaps the only one — of Soviet light industry. It is unsurprising that military uniforms and military paraphernalia were in high demand among foreigners, and

were reinterpreted by amateur fashionistas.

The persecution of fashionistas and the rejection of the un-Soviet way of life had begun during the World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow, when ideologically correct citizens began to criticize the stilyagi (or what we might think of as hipsters).

In the 1970s, the Soviet aesthetic came under attack from fashionistas and black market retailers and the first subcultures of hippies and beatniks. In the 1980s — at the same time as the first wave of fashions popular among music lovers hit the Soviet Union, and were persecuted just like rock music — a host of subculture movements appeared on the streets. Entire street tribes were formed, as were clothing styles that corresponded to people’s musical preferences.

This all took place in the pre-perestroika period, and the press began to energetically demonize the new, “un-Soviet” citizens and

their “derivative” fashions. But again the state was mistaken: In these subcultures, which developed in relative isolation, personal

approaches to fashion, and not imitative ones, were cultivated. On one side in this fashion rebellion was the decrepit nomenklatura, attempting to control the Soviet Union’s ideology and daily life. The other side boasted not only fashionistas and consumers but also people well-educated in design and production. The latter were able to both discover new ideas and bring them to life.

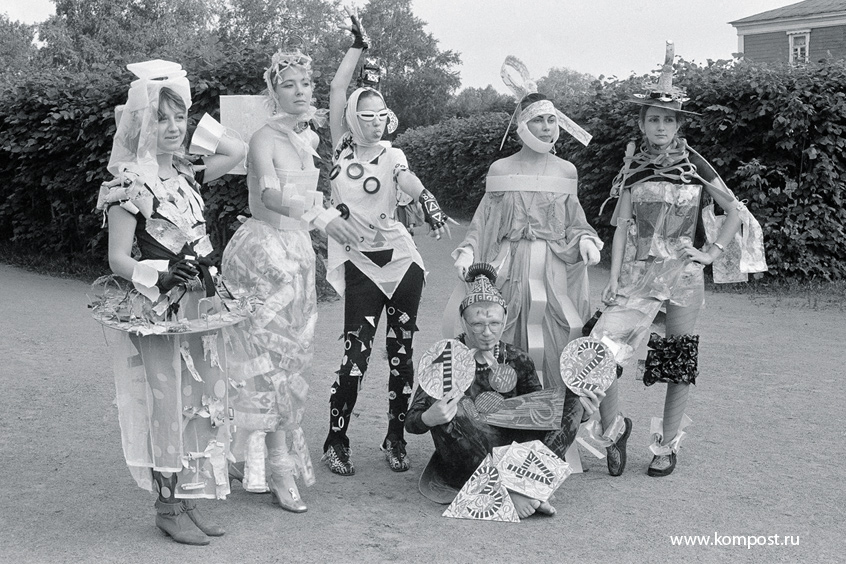

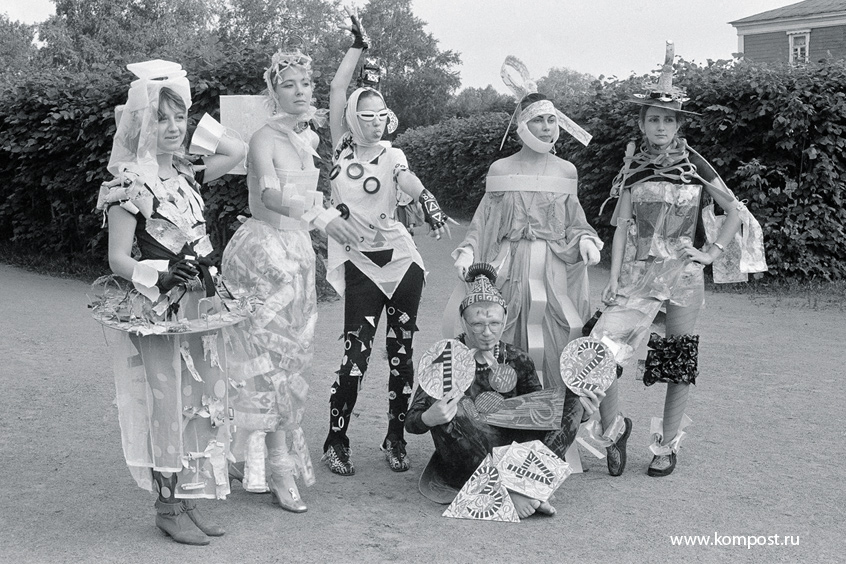

Amateur fashion blossomed on student scenes in the 1980s.From the ranks of these uninhibited students-cum-artists emerged new, alternative designers. Some looked to the avantgarde artists of the 1920s, and were not concerned with real fashion. They mostly built architectural constructions from non-traditional materials such as cellophane and foam. Others, in large part students from the Moscow Architectural Institute and the Printing Institute, tried to make wearable and ultramodern clothing, despite their avant-garde leanings. There were also those who took inspiration from the practical experiments in Soviet fashion that took place during the 1920s, when the ingenious Nadezhda Lamanova and the constructivists built a new Soviet aesthetic.

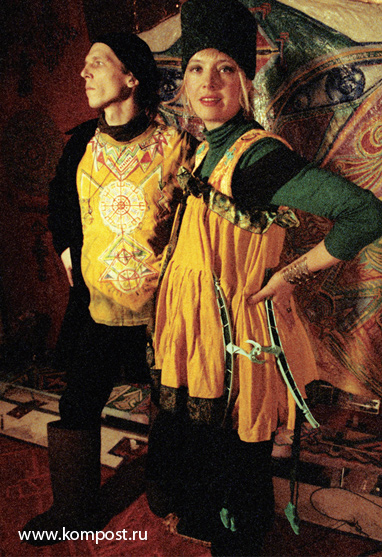

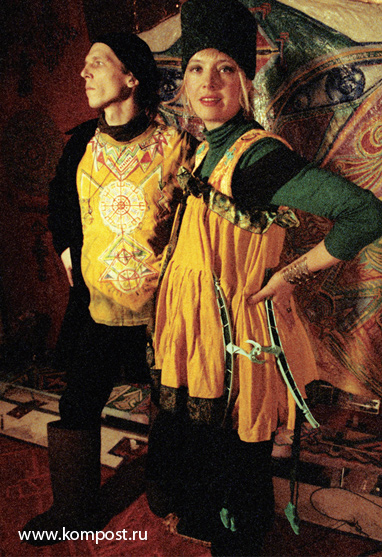

Thus Yelena Khudyakova, a student at the Moscow Architectural Institute, began by reconstructing outfits based on sketches by Lamanova and Varvara Stepanova, and went on to adapt these “functional” designs to contemporary realities. The result was completely wearable, modern clothing. Khudyakova was fascinated by the early Soviet aesthetic, and was one of the first to rework Soviet uniforms and even took a bite out of that era’s forbidden fruit — she reinterpreted the style of Josef Stalin.

Khudyakova was also involved in producing accessories using elements of army uniforms.In her reworking of the uniform of Soviet workers, Khudyakova did what designers at the fashion houses still had not accomplished: She reimagined and adapted, with reference to the trends that reigned in the 1980s, a key element of folk fashion, the quilted jacket. It was a cult item among teenagers and in the suburbs (and was an essential part of the wardrobe of the proletariat and Soviet prisoners).

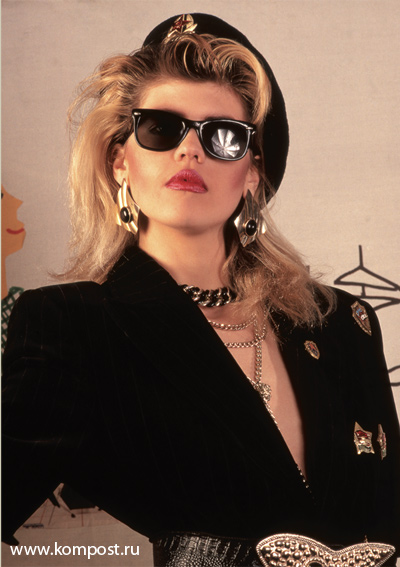

Alternative fashion was in many ways derived from rock culture, a subculture that produced its own designers. One, Irina Afonina, was a professional dressmaker, and for some time she worked at the All-Union Fashion House. But she also outfitted numerous rock musicians, and during perestroika she created a special collection of alternative clothing for an Italian who planned to open a store selling Soviet clothing in Italy.

With the onset of perestroika, these changes affected the world of official fashion. A significant role in the transformation of the state fashion industry was played by Raisa Gorbacheva. The wife of the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union became a style icon for many Soviet women. The First Lady took the House of Fashion on Kuznetsky Most under her wing, and invited Pierre Cardin and Yves Saint Laurent, and their fashion shows, to the Soviet Union, as well as the “principessa of fashion,” Irene Galitzine. Gorbacheva also enabled the fashion magazine Burda Moden to begin publishing in the Soviet Union; it organized the first beauty contests in the country, and from 1988 they became a tradition in many Soviet cities. She showed her loyalty to alternative fashion by protecting it from attacks by the Artistic Council and sanctioning a fashion show in the concert hall at the Rossia hotel.

Alternative fashion developed spontaneously, according to the spirit of the times: The old world collapsed before people’s eyes, and a new one appeared amid the universal chaos. The destruction of the Soviet empire was accompanied by powerful bursts of creative energy, and fresh blood re-energized the art world. Young artists, drunk on the atmosphere of freedom, created what was perhaps art rather than fashion, and worked without looking to Western brands for inspiration. Cropping up like wildflowers in squats and on the streets, alternative fashion destroyed the notion of the “Soviet person,” poked fun at everything sacred to the state, provoked the Soviet people, and in many ways became an analog to Sots Art. Alternative fashion was part of underground culture, together with rock music and visual and performance art. It developed amid the various subcultures and was produced with an eye toward the many styles of street fashion. For punks, hippies, metalheads and New Wavers, external appearances were not only a form of self-expression but also a way to differentiate themselves, the freedom-loving non-formalists, from the Soviet masses. Moreover alternative fashion became a rebellion against the “fathers,” against the older generation with all its characteristic conformism. With no other choices open to them, every fashionista became a designer.

The first flashes of alternative fashion could be seen at the so-called assa shows, which emerged in the St. Petersburg underground. An assa was a group happening that mostly took place at performances by Sergei Kurekhin’s Pop-Mechanics group. At these rock ‘n’ roll gesamtkunstwerks, participants included rock musicians, non-formal artists, poets and even animals. They also featured shows of alternative fashion, which were thought up by the partygoer Oleg Kolomiychuk, who was given the nickname Garri (or Garik) Assa for his contribution to the movement (it became his pseudonym). These colorful, artistic events in the Soviet underground began to attract the attention of the Western press and local photographers and directors, who were paying close attention to the changes occurring in the Soviet Union during perestroika.

Sergei Borisov

I first took photographs of my outfits,and then periodically did sessions with Katya Filippova, Gosha Ostretsov and Katya Ryzhikova; I felt in my skin that the avant-garde would be in demand.And that’s what came to pass. It was a period when, over the course of several years, the Western press trumpeted the Soviet Union, the photographs were snapped up everywhere, even duplicates, and I ran out of film like a machine gun goes through its magazine. In 1987 I was telephoned by a German journalist who proposed publishing the photographs in Tempo magazine. They intended to write about perestroika, but they didn’t have any good visuals. During a meeting I handed over a packet of 40 slides to their correspondent. Ten days letter the entire editorial staff approached me with a request to show THIS life. They came with a flat plan of the magazine and with the the magazine cover, which had already been printed. On the cover was “my” girl and the subhead: “A remarkable Russian review.” The next year, Tempo, Actuel and Face formed an association. I became friends with them, and when the magazine came out everyone was very impressed.

A former black marketeer, charismatic and with a remarkable sense of style, Garri Assa became a trendsetter on the underground scene, producing stage and everyday looks for rock musicians and partygoers. For the Pop-Mechanics events he created the improvised fashion house Oh-Yes-People, and its shows were like a noisy, punk circus. A distinctive stylist, he boldly combined clothing of various styles and epochs that he found at Tishinsky market. He was the first to discover the Moscow flea market, and brought vintage into fashion. Assa was part of the St. Petersburg underground, and was appointed minister of fashion in the government organized by the New Artists group. Aside from the assa shows in Leningrad, L.E.M. ( the Laboratory of Experimental Models)was formed behind Rock Club, under the asisstens of the

artist Kirill Miller and colloboration of the avant-garde designers

Sergei Chernov and Svetlana Petrova, who take mission about future

shows of L.E.M. , since 1989 till today.

Svetlana Petrova

The L.E.M. came about not as something spontaneous, it was a vanguard, a purposely made up and engineered phenomenon– it was post-alternative, the reflection over alternative, just like there is, for instance, post-graffitti. You didn’t have to be a party-goer or a designer to create L.E.M. My and Pete’s scientific research lay in the field of cultural anthropology, and we treated the party-crowd as Levi-Strauss

the autochthons or as Spengler the historical facts.

There’s nothing wrong about it, it’s just an approach. L.E.M.

is the same cultural anthropology, it’s my first experiment in this

very rare genre that I would call the “creative cultural anthropology”.

But

yet you can’t say that L.E.M is not fashion: the concept of

“trendiness, actualite” is a feature of my creativity, it’s present in

the subsequent projects as well. It’s not even “trendiness”, rather

“Zeitgeist” – the time-spirit taking the form of mass interest in some

event. Alternative fashion should be

As well as working on looks for rock musicians, the laboratory organized fashion shows under the slogan “It doesn’t matter what a person wears, what matters is that he can be dressed.” And hey did indeed dress people in everything, from cast-iron slabs to bicycle wheels.

Assa became acquainted with the Moscow artistic scene at the Kindergarten squat, where the first shows of alternative fashion in the capital were held. Garik brought the “dead spy” look into fashion among non-formalists — it entailed wide trousers gathered in folds at

the waist, giant jackets with rolled-up sleeves, double-breasted coats and “pirozhok” hats, or basically things from the wardrobe of the Soviet nomenklatura. The look got its name from the fact that this kind of clothing was brought to the Tishinsky market by the widows of Soviet spies. Assa also brought the assa events to Moscow, where they were supported by local artists and fashionistas.

Garri Аssа:

"Having settled in Moscow, I discovered Tishinka, where they were selling stylish jackets, tunics and Chekist uniforms. Today the quality of these things is considered remarkable, but few really understand this even now, and back then no one at all was interested in them. We began to buy up these «spy suits,» dressed up in them and organized derisive performances on the streets. The ostumes necessitated a special way of carrying oneself thatlooked clownish. That’s how the «dead spy» style came about. When it comes to actual clothing there is nothing left to create, so for novelty you need the ability to create all sorts of mixes and to wear unthinkable accessories. You could sew something yourself, but why? There were already ready-made things, though they were hand-picked and had their own history. The looks created by my fashion house, Oh-Yes-People, were intended to shock and stun. Strutting about with underpants on top of your trousers or with a plastic bag on your head was a gesture made both with regard to the item and to the audience. It was for good reason that Oleg Kotelinkov gave the following slogan to my fashion house: «Clothing is my earthly complex». This whole process, which went on for 20 years, allowed genuinely talented people to realize their ambitions and become stars. We simply tried to inject Soviet life with a completely un-Soviet culture, and this bore distinctive fruit once it merged with real Soviet life. It is possible that it was not the time for such experiments, because the consciousness of people in such a giant country only changes with difficulty and at a slow pace."

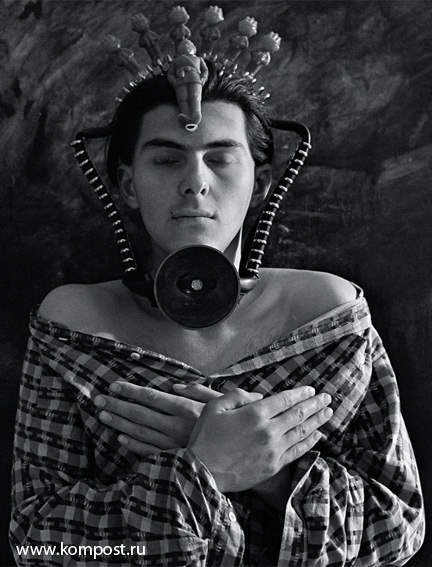

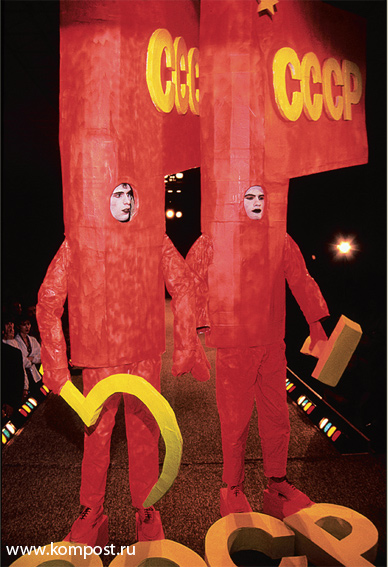

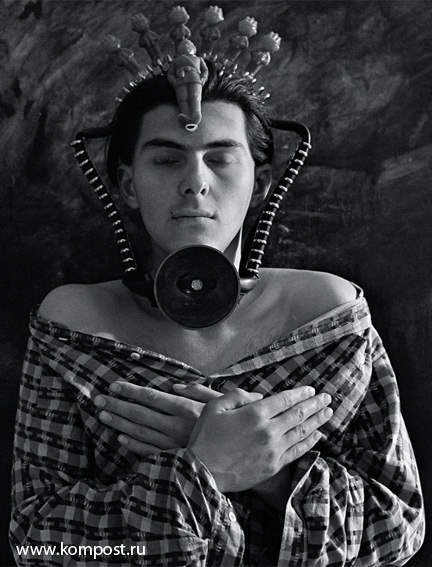

The artist Gosha Ostretsov was one of the inhabitants of the Kindergarten squat and became involved in alternative

fashion partly under the influence of Garik Assa. But compared to Garik’s relatively wearable punk prêt-à-porter, Ostretsov

created looks that were not at all intended for everyday use.

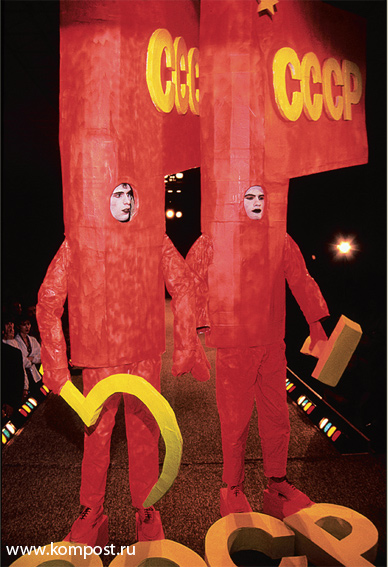

In his first collection he made ironic outfits for communist conquerors, in the spirit of the avant-garde film “Aelita,” but

with an obvious touch of Sots-Art. His “War” collection was dedicated to the migration of communism to other planets. This

was an understandable desire during perestroika, when this was the fervid dream of millions of people. But the collection also

unambiguously mocked the military might of the Soviet army and the idea of world revolution — and in 1987, such jokes were

not for the faint of heart. In the appearance of the conquerors of the cosmos there is something obviously infantile. Their outfits

were decorated with children’s toys and even constructor sets — there was a cap made of an upside-down plastic children’s potty,

toy tanks instead of epaulets, and the captain’s coat tails had a toy airplane at the end.

These costume performances did not only take place in squats and galleries. Ostretsov turned his own wedding into

a carnival — the bride and groom, in superhero costumes, registered their marriage as volleys were fired from toy

machine guns.

Gosha Ostretsov:

I was not engaged in fashion but rather costumed Gosha Ostretsov performances in the style of the “blue blouses,” in which the

theme of hypercommunism was developed by myself and Timur Novikov. Music and performance were united, as in the first parades of the 1920s. In my case the New Wave overlapped with the aesthetic of naive art that enjoyed popularity in the mid-1980s. It was a conceptual descent into childhood.

Children’s toys were used as elements of outfits, and in the next collection there were bracelets made from the rubber treads of ski boots and the little wheels from the chassis of toy airplanes. The toy theme was continued in the shoe collection, which I created for Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, but with motifs from traditional Bogorodskoye toys. I work with Castelbajac for several years when I lived in France, as well as with Jean-Paul Gaultier and Kenzo. In art I create a conceptual environment of play. As regards the place of the artist, I think that the artist should go beyond just working on an easel and should be its continuation, broadening the space of its impact.

The enthusiasts involved with Garri Assa’s whirlwind of shows were infected with his irrepressible energy and soon revealed their own creative sides. Garri brought in two of his friends to participate in the assa parades, the students-cum-fashionistas Katya Ryzhikova and Irene Burmistrova, who had become jaded with the foreign clothing obtained from black marketeers. The girls first participated in the shows as models, and later decided to try their hand at design. The “Blood and Milk” group formed by Ryzhikova and Burmistrova was initially focused on a futuristic line of clothing that was impossible to wear in everyday situations.

Their first collection, “Iron Shovel,” was in the spirit of Sots-Art and included Soviet symbols such as shovels, forks and other agricultural tools. But Burmistrova and Ryzhikova soon began to work separately. Burmistrova was drawn to futuristic architectural forms — her models wore fantastical constructions made of non-traditional materials such as plastic, cellophane and foam. It was rumored that at the end of the 1980s, she sashayed in her “Rocket” outfit around Red Square and was briefly arrested. The last joint project by Burmistrova and Ryzhikova was shown at the “Art-Rock Parade Assa,” an avant-garde presentation that took place at the premiere of Sergei Soloviev’s film “Assa,” soon after which Burmistrova left the Soviet Union.

Katya Ryzhikova found her way into alternative fashion by participating in the assa parades, and then continued her line of “dramatized” costume performances. At the end of the 1980s she took part in presentations by the avant-garde POST Theater, which was organized by Kamil Chalayev and Gor Chakhal; as a result, many participants of the assa parades were also drawn to it. In her first avant-garde collections, Ryzhikova ironically combined ethnic elements with a pseudo-industrial style, and went on to perfect her approach by uniting archaic forms with transculture. At the end of the 1980s she joined the North group, which staged performances inspired by shamanic and neo-pagan tribes, featuring fire shows and avant-garde musical accompaniment. North focused on neo-primitive motifs, building huts in urban areas, roasting meat and drawing cavemen, and any visitor could participate in the process, making pictures and painting the other residents. To makes costumes for alternative matryoshkas and mermaids they used pipes, skiing accessories, children’s yellow and turquoise plastic flippers, and some outfits even featured embroidery. When rock music was replaced by raves, costumes made of futuristic constructions turned into talisman-costumes. The designers were helped in this regard by the discovery of rare items at Tishinka.

Каtya Ryzhikova

When people ask me what exactly we were involved with, I think that the most correct answer is — childhood traumas. When I was invited to take part in an exhibition of avant-garde fashion at the Manezh, there was a scandal at the opening. My outfits displayed in the windows so stirred the imagination of one representative of the post-Soviet fashion industry that she became hysterical and started running into the window, screeching and beating the glass.

I then had to pay a fine for the broken glass, and I stopped being invited to official exhibitions.

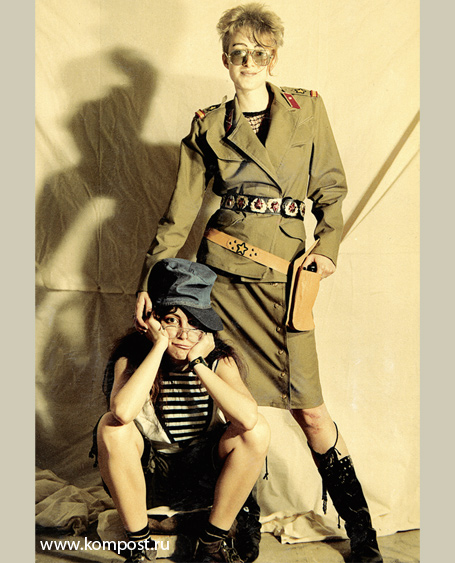

The designer Katya Mikulskaya, subsequently Mossina, was a student at the Moscow Architectural Institute in the 1980s and was celebrated for her glamorous riffs on military style.

She offered caps bought at Tishinka, rough boots, flight helmets and, most importantly, soldier’s tunics. Mossina transformed these authentic soldier’s tunics from Tishinka into cocktail dresses — she cut away the cuffs and backs, dyed them in the then-fashionable acid colors, and selected authentic accessories, such as genuine sword belts. She sewed tiered skirts out of red flags, and they were reminiscent of curtains in colonnaded Soviet halls. Her top seller (and it is important to note that the buyers of clothes by these designers were mostly foreigners) was her “dress in a jar,” which the young artist pushed inside a three-liter cucumber jar to give it a fashionable wrinkled texture. And there was no better way of expressing derision for Soviet bureaucrats than her “pirozhok” hat, which, with a quick flick of the wrist, transformed into a bra. The weighty object made of Persian lamb fur had a zipper sewn in the center that could be opened, meaning that at fashion shows it metamorphosed from the hat worn by the nomenklatura into an ultra-fashionable fur bra. In the same ways shoes were converted from something commonplace into something exclusive. Mossina took heavy boots on thick soles, known as “tourist boots,” and applied bronze paint to them. The result was avant-garde Soviet glamour.

Katya Mossina

In my interpretation of military uniforms some saw the blaspheming of military history, while others saw the path to emancipation. As one Western journalist wrote, Katya Mikulskaya merges MTV style with images of the tsarist past. My desire to surprise was more powerful than my desire to show fashion. All our new wave was oriented toward the creation of new forms.

Young, fashionable designers conquered the official podiums as well as the unofficial stages that hosted assa shows. At that time the main bastion of Soviet fashion was the Fashion House on Kuznetsky Most, where alternative designers staged their first official show. The show was organized by the music critic Artemy Troitsky and a young employee of the Fashion House, the master of ceremonies Svetlana Kunitsyna. They proposed comparing official and unofficial fashion, alternating between displays of official and unofficial outfits. It’s fair to say that the performance staged by the Soviet “new wild ones” had little in common with a fashion show. The show was cynical defilement of the official style of fashion shows, and employees at the Fashion House were fairly shocked, although they were far from sanctimonious people. The alternative designers Katya Filippova and Katya Mikulskaya (later Mossina) appeared with rock groups, Central Russian Upland and Sounds of Mu, the soloist of which, Pyotr Mamonov, terrified Soviet designers and models with his tough outsider image. The stage was decorated with vivid pictures in the New Wave style by the artists Zhora Litichevsky and Gosha Ostretsov. And there were jokes: During the show, a female model chucked a cake into Sven Gundlah (vokalist Central Russian Upland) face. At Katya Filippova’s first show, a bulldog in leopardskin velvet and a tie played the role of a model. There was soon a second show of underground fashion, organized by Svetlana Kunitsyna at the editorial offices of Fashion Magazine, where Zhora Litichevsky’s collection “Osvod ” and a collection by Katya Mossina were shown. In no time at all, alternative designers were showing their work at more important official shows.

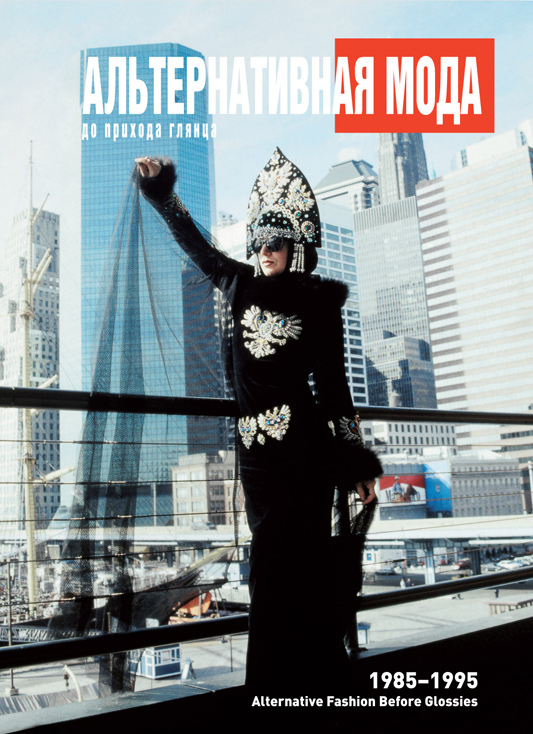

Katya Filippova created her first collection for a festival of alternative fashion and music that took place at the Fashion House on Kuznetsky Most. But her mature style was demonstrated at British Fashion Week at Sovintsentr, when she, as the only Soviet designer at that time, was invited to take part alongside world-famous designers, including Vivienne Westwood. In the first part of Filippova’s collection, punk flirted with a tsarist style. Kokoshniks embroidered with double-headed eagles were combined with punk bras in leather, and fur caps were covered with long, black veils. The outfits were studded with pearls, stones, crystals and glass beads, which added glamor to this contemporary version of Russian Gothic. The second collection, in a Sots-Art style, was called “Major Stogov’s Nightmare.” The collection received its unusual name after the inscription “Major Stogov,” written in ballpoint pen, was found inside one of the military uniforms. There is no doubt that this extravagant collection might have appeared to the major in a nightmare. Military tunics were transformed into jackets with tails of lace, like a giant train, and were embroidered with stones. Red ballet tutus could be seen underneath the uniforms (and after all, Soviet ballet was known as “red ballet”). The look was completed by a handkerchief cap, which for Filippova was as much a symbol of femininity and sexuality as the Russian kokoshnik. Flippova prevailed on Russian catwalks right up to the end of 1990s.

Кatya Filippova

I’ve always loved the Byzantine luxury of churches. I grew up alongside this beauty. My great-grandmother made church vestments. And I was undoubtedly inspired by images of tsarinas — in graphical art, mosaics, painting or fashion.

As a result I invented the name tsarism for my style. It was as much an “ism” as Impressionism or minimalism. I focused on the tsarist theme in fashion, which is the only beautiful theme in Russian costume, and after all, Russian peasant women are also tsarinas. My tsarinas are tsarina-punks in exile. In my soul I have always been a punk. Not the kind that spits and drinks beer. Not a carbon copy of the Sex Pistols.

But I was very drawn to “punk” in the sense of rebellion. I think that of all the 20th-century fashions it is the most everlasting, and when it is reworked it looks the most elegant. We used this aesthetic both in life and on the catwalks. There was a striving for nobility and a love of luxury, the shimmer of which emerged as a protest against the poverty that surrounded us.

We wanted beauty, emotion, we wanted to shock. I shocked the audiences by combining Soviet military forms with ballet tutus, and communist and religious symbols, but at the same time I tried to emphasize the connection of ideology in Russia with fundamental institutions like the military, monarchy and religion.

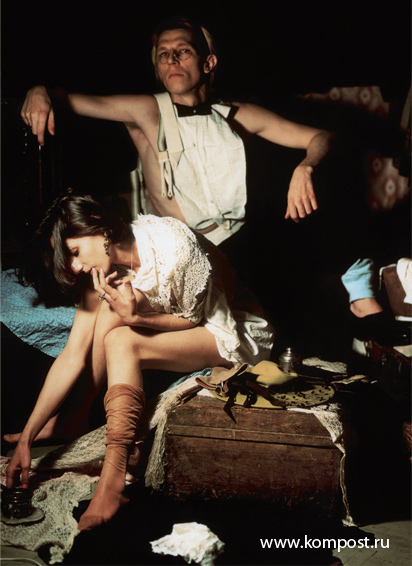

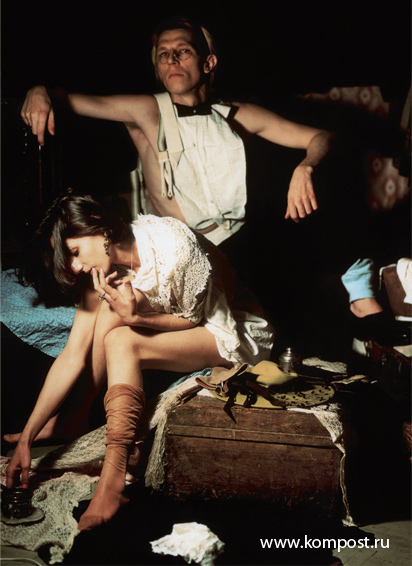

At the end of the 1980s, the artist Alexander Petlyura continued the vintage branch of alternative fashion. Petlyura became a true connoisseur of vintage and was a frequent visitor to Tishinsky market. He used his vintage treasures for fashion performances at the Moscow squat he founded, on Petrovsky Bulvar. Clothing was a kind of paint in Petlyura’s art-performances, and he created theatrical productions. The star of the Petrovsky squat was Pani Bronya — Bronislava Anatolyevna Dubner, who lived on the territory of the squat with her husband, Abramych. The elderly lady responded with remarkable equanimity to the experiments of the young artist and became the talisman of Petrovsky squat, as well as Petlyura’s muse and model. The squat’s most notable production was “Snow Maidens Don’t Die,” based on the Ostrovsky fairy tale, in which Pani Bronya played the main role. The apotheosis of the collaboration between Pani Bronya and Petlyura was their well-deserved victory at the Alternative Miss World 1998 competition.

Later Petlyura put together the “Empire in Things” project, or, as he calls it, “a lifelong installation.” It featured 12 collections of vintage things dating from the beginning of the last century to the end, and was organized into thematic groups. Thus, with the help of clothing, Petlyura created the most unusual history of 20th-century Russia in 12 “volumes.”

Alexander Petlyura

When Bronya and I arrived at the Alternative Miss World competition, no one took us seriously. During the first part we had to show a “day” dress. I remembered the Volgograd monument “The Motherland Calls” by Vuchetich, who gave a sword to a grandmother, and so I called my first look “Mother of the Hero.” Bronya came out with a sword, in a dress by Christian Dior of gold brocade, with a mask pulled off her face, and on her head she had a scalp sawn off from a doll. For her second look I dressed Bronya in a mermaid costume, sewn during a night at a friend’s apartment, and I played the role of a water sprite. Her costume was covered with gold — the pubis,

the nipples, a wig made of copper wire, and in her mouth was a green branch. I stuck flowers everywhere — in her mouth, her bottom… I finished the look with flippers. It got crazy, but something was still missing. The third look was called “The Pink Dream of a Blind Musician.” I came out in a toreador costume (I bought a jabot at Portobello), and on my feet I had pink boots. I dressed Bronya in an expensive wedding dress and gave her an enormous quiff. At first the audience thought she was a transvestite. I was led in by my arm like a blind man, in pink glasses, and they started playing Gipsy Kings. Bronya came out, and when everyone saw her face they realized she was a woman. And an eternal and everlasting child. And she took a spin with such naivete, like a doll in a box. It was a shot to the heart. The people in the hall both cried and laughed. It was a new genre for them — the Soviet folk simpleton.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the onset of the 1990s, the paradigm of alternative fashion shifted. While in the 1980s, alternative designers positioned themselves in opposition to the archaic style of Soviet official fashion, they needed a new target following the destruction of the state institutions. In the 1990s designers directed their energy against mass-produced Chinese goods, post-Soviet cooperative kitsch and the first glimmers of glamor. The aesthetic of decadence and rave culture replaced aggressive rock stylings. Partygoers began to study and collect vintage clothing, and club culture was enriched by people dressed in a Soviet naive style — ski and botanical engineer costumers created a furore, and there was massive demand for Soviet children’s things — caps,

mittens. At the Petrovsky Bulvar squat alternative fashion had a second wind and found new adherents. New names appeared

in the history of alternative fashion along with the Petrovsky squat — Alexander Petlyura, Olga Soldatova, Masha Tsigal, the Polushkin brothers, Andrei Bartenev. And clubs as well as squats became arenas where new fashions could be shown off — they included vintage looks as well as the “acid” looks that emerged with the raves.

Starting off as models for Irene Burmistrova and Katya Ryzhikova, Larisa Lazareva and Regina Kozyreva formed the La-Re group and embarked on careers as designers. La-Re continued the futuristic emphasis of alternative fashion, but aside from their use of nontraditional materials they stood out mostly for their technological focus. Every look was conceived of as an object in which a life

philosophy had been embedded, with a touching female subtext. Despite the use of unusual materials in their clothing, for example

in the looks made from swimsuit cups or chipboard sawdust, the duo were drawn to sophisticated and feminine forms. The pinnacle of La-Re’s feminine style was the “Eyelashes” collection, in which floor-length evening dresses were decorated with giant eyelashes made of artificial snow. Obtaining such an exotic material in the 1980s was practically impossible, so one of the group’s fans was forced to crawl onto the ski jump at Sparrow Hills at night and fleece chunks of artificial snow. Many of the duet’s costumes had kinetic qualities. The most interesting collection, with a technological focus, was the cyberpunk collection “Don’t Lose Time,” which was almost the duo’s last.

A veil movements were ruled by a remote control, watches were embedded in boots with plastic soles, balls fell out of outfits —

in a word, everything moved and changed. The duo took part in numerous fashion shows — at fashion festivals, clubs and stages on Petrovsky Bulvar — and ceased to exist at the end of the 1990s.

Larisa Lazareva

I think that our style could be called “glamorous punk.” We created outfits from the strangest materials, but we used them as aesthetically as possible. It was also important to us that the costume, its construction, should work like a mechanism. Our first collection, “Love is…” was dedicated to the various manifestations of love and featured four outfits. We called the first dress “Wedding — one day.” The wedding dress was sewn from protective padding made of polypropylene foam, the kind that is used in computer boxes. We were saying that a wedding is a onetime event, but that it is crazily labor-intensive. The second dress was called “Iron Lady” and was dedicated to Margaret Thatcher. It was an aggressive thing made of metal constructions. The third, “Love is Winter,” was sewn together out of furs we had bought, and had lace inserts hand-decorated with flowers. Our shows always featured animals — rats, rabbits, birds, fish. The model in the “Love is Winter” outfit came on stage with a bird in a cage. More than one bird has died a hero’s death — the nomadic life turned out to be too much for them. We also had a wonderful rat dyed every possible color. We showed it at an exhibition at Tishinka, where we suggested buying pipettes tobe used as condoms, in order to protect the health of female rats and prevent them giving birth too many times.

At the beginning of the 1990s, La-Re began to collaborate with the Az-Art gallery, founded by the journalist Inna Shulzhenko. The gallery supported the duo, allotting them money for manufacturing and for shows in relatively exotic locations, such as factory workshops, where models paraded to the roar of working machinery. With support from Az-Art, La-Re tried to put fashion on an industrial track. After an order from the gallery, Larisa Lazareva made an industrial collection, “I’m Visible,” which was wearable. Shulzhenko collected an entire archive of the avant-garde duo’s work and tried to initiate production of their clothes using a Russian clothing manufacturer, but because no one had any experience in this area, there was none of the necessary oversight. The clothing produced by the manufacturers was not only far from what the designers had intended, it was also impossible to wear. Efforts to work on an industrial scale were a failure. The designers had collided with the same problem as Soviet designers — the impossibility of bringing their designs to life in Russia, because that would require a certain level of technical mastery. Moreover Soviet light industry had simply collapsed. The industrial-scale production of designer clothing, in large part accessories, only became possible at the beginning of the 2000s.

In the Soviet Union the Baltic states played the role of foreign countries, and the Tallinn Fashion Week was the most professional and prestigious event in the country. But it was in Riga rather than Tallinn that the alternative fashion movement arose, headed by Bruno

Birmanis. In 1987 Bruno, with Ugis Rukitis, created his first collection, and soon a group of enthusiasts formed an actual theater, and they toured the entire Soviet Union with a fashion performance called “The Ball of Post-Banalism.”

The political changes that roiled the Baltics inspired the young artists to create a collection in the style of Sots-Art — a brave collection of prison overalls intended for artists, policemen, prostitutes, priests and other categories of citizens. In 1989, Bruno Birmanis managed to organize a large-scale event — an Assembly of Untamed Fashion. The assembly’s first event was attended by a star of British alternative culture, Andrew Logan, and although another legend of alternative fashion, Zandra Rhodes, was not able to attend in person, she sent an entire collection of dresses with Logan. There were already numerous orders by the time of the second assembly, and Red or Dead, a hip, hooligan-fashion company from London, took part. The contrast between the Soviet delegates and

the foreigners was initially very noticeable, but gradually designers from the post-Soviet space progressed and the difference was erased.

Bruno Birmanis

Alternative fashion comes exclusively from the emotions, and it doesn’t have any relation to fashion based on patterncutting.

It is declarative art. In a general cultural sense the assembly, which took place for several years, created a discourse about the fact that alternative fashion existed and was interesting to the general public and magazines. In a purely practical sense it was a separate niche for artistic statements within the realm of fashion. Even taking into account the degradation of industry and the absence of haute couture in the post-Soviet space. It was both a show and a form of communication for realizing creative ambitions. Together with the assembly, Latvia saw the emergence of an alternative and powerful understanding of fashion, and for the average person it was an event that encouraged numerous tourists to visit, including famous foreigners, notably Paco Rabanne. Airplanes jam-packed with guests flew to our events in order to see what “untamed fashion” was all about. Media attention fueled these developments,

and the event seriously increased the diversity of cultural life.

Despite the fact that attention in the post-Soviet space was oriented toward the West, the assembly stimulated interest in fashion on a different vector, “West-East.”

Andrei Bartenev became involved in the alternative fashion movement at the end of the 1980s. Like Gosha Ostretsov, Bartenev was not working in fashion per se, but in the genre of costume performance. Inspired by the performances of German Vinogradov and an exhibition of remarkable constructions by Jean Tinguely, he created his own kind of costume-object. Following the success of his first production, “Wrapped-up Doll,” Bartenev took part in the Assembly of Untamed Fashion in Riga in 1992 with a production named “Botanical Ballet,” which created a furore. The costumes were made of papier mâché, decorated with white water-emulsion paint, and the black had to be formulated by mixing ink and varnish, which gave the appearance of mica. Bartenev was inspired by his childhood dreams: He was born in Norilsk, above the Arctic Circle, and dreamed of fruit, which he would mold out of snow. “Botanical Ballet” featured apples, cherries and Bartenev himself in the costume of Uncle Prune. There were other characters in this winter garden extravaganza who were linked in an abstract way to the theme: Arnold Nizhinsky; “Glasnost Booth”; “The Snowstorm Girls,” a double character wearing kokoshniks; as well as some rather more fantastical figures: “Mallet” wearing a headdress named “Karyaksky Thermoelectric Power Plant-1”; and “Submarine” in the headdress “Karyaksky Thermoelectric Power Station-2.” They spun around the stage in a waltz under a snowstorm.

Andrei Bartenev

Ar t i s t i c l i f e r a g e d in Mo s c o w and Leningrad. I began to mine this deposit just as it all started to die down, but I knew that these people were very brave. The atmosphere at the end of the 1980s was romantic and heroic. The situation propelled everyone to embark on some new feat and drew them into the whirlwind of events. Everyone had to practically sacrifice their life for the sake

of something unconscious. And everyone created activity around themselves; no one went with the flow.

The adventures of avant-garde artists in the fashion industry ended differently for each of them — each person chose their own path. For many, the story of alternative fashion ended with the arrival of Western glamor and the new stagnation of the glamorous noughties. Some became collectors of extravagant vintage things, while others returned to pure art. But many who emerged in the alternative-artist movement were able to secure a place for themselves on the market as designers. The Russian fashion movement has proved surprisingly tenacious — after the closing of clubs and squats, the former epicenters of fashion, and following three financial crises, fashion is still alive. Experiments by young designers and street fashion remain viable alternatives to the present-day official fashion weeks. Still, the experiences of alternative designers are half-forgotten and undervalued, like many avant-garde phenomena. It is possible that the time has come to reevaluate our relationship to Russian alternative fashion, to reconstruct this unique happening, which has no analog. Currently a publication is being prepared that will tell the history of Soviet official, black-market and alternative fashion during perestroika.

Misha Buster

Elena Fedotova

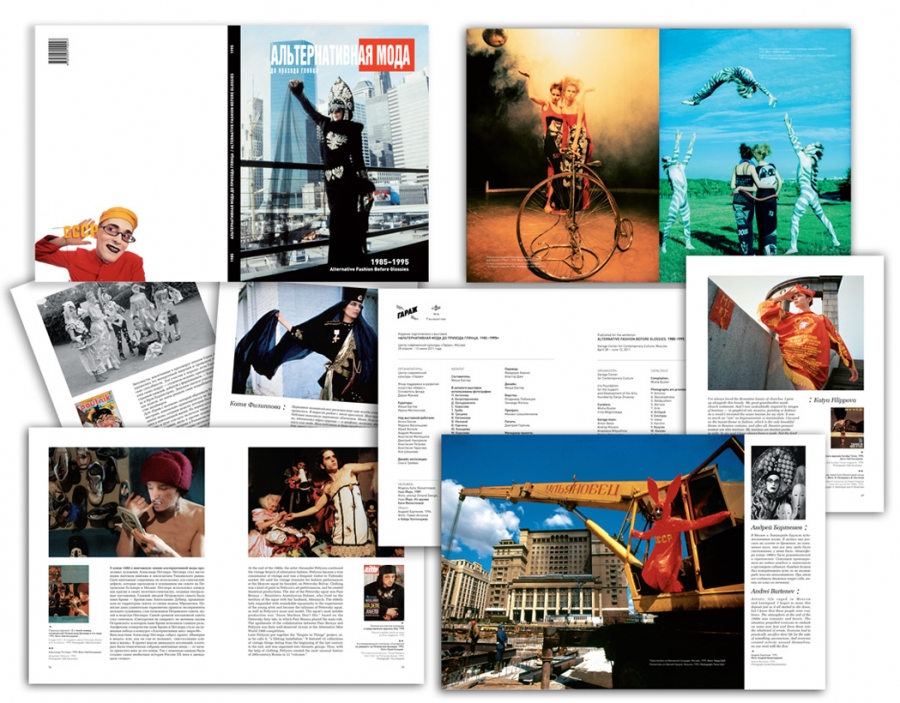

Published for the exhibition

Alter native Fas hion Bef ore Glossies . 1985–1995

Garage Center for Contemporary Culture, Moscow

April 28 – June 12, 2011

Organizers:

Garage Center

for Contemporary Culture

Iris Foundation

for the Support

and Development of the Arts,

founded by Darya Zhukova

Curators:

Misha Buster

Irina Meglinskaya

Garage team:

Anton Belov

Andrey Miziano

Anastasia Mityushina

Dmitry Nakoryakov

Anastasia Petrova

Asya Shishkova

Anastasia Tarasova

Marina Vasiltsova

Yury Volkov

Exhibition design:

Olga Treivas

CATALOGUE

Texts:

Misha Buster

Elena Fedotova

Editor:

Ekaterina Allenova

Project manager:

Danila Stratovich

Production:

Art Guide

ISBN 978-5-905110-04-7

Design, texts and images

© M. Buster

© Art Guide

Printed by August Borg

47 Verkhnyaya Pervomaiskaya ul.,

bldg. 11, Moscow, 105264

|